For decades, the Peruvian timber sector has been rife with criminal activity, tainting domestic and global supply chains, perpetuating unsustainable logging in the Amazon, and harming Peruvian communities. New analyses of Peruvian customs records and forest inspections by both the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) and by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) confirm that a large percent of Peru’s wood exports were cut illegally, with complete disregard for laws and sustainability.

The United States, the third-largest importer of Peruvian timber, has recently taken strong actions to interdict the entry of illegal Peruvian timber. 1 Office of the United States Trade Representative (20 October 2017). USTR Announces Unprecedented Action to Block Illegal Timber Imports from Peru. Press release.

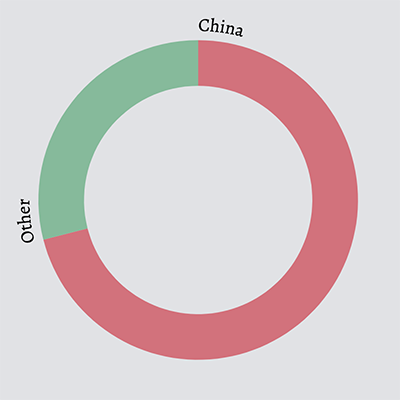

China, Peru’s largest timber trading partner, is also the buyer and consumer of the majority of Peru’s illegal timber.

Data shows that large percentages of Peru’s timber exports are from illegal sources

Illegal logging has plagued Peru’s Amazon forests for years. In 2002 the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) estimated that “anywhere between 70 to 90% of all timber coming to the market is illegally harvested.” 2 “Achieving the ITTO Objective 2000 and Sustainable Forest Management in Peru – Report of the Diagnostic Mission” In 2006, the World Bank estimated that 80% of Peruvian timber was illegally cut. 3 Goncalves, M.P. et al. (2012). Justice for forests: improving criminal justice efforts to combat illegal logging. The World Bank. And in 2016, the Peruvian government’s forest oversight agency, Organismo de Supervisión Forestal (OSINFOR), reported that 78% of the wood inspected between 2009 and 2016 came from illegal sources. 4 García Delgado, F. (15 Sep 2016). Osinfor: 80% de inspecciones contra tala ilegal irregulares. El Comercio.

OSINFOR conducts post-harvest assessments of logging areas around the country to determine whether harvesting was conducted legally. Inspectors publish their findings on a public database 5 Osinfor. SIGO-SFC database :

http://www.osinfor.gob.pe/sigo/ , and classify particular logging operations as either “green” or “red.” “Green” harvesting operations contain no major violations, though they often contain minor violations that are detailed in the inspectors’ reports. A “red” designation indicates that inspectors found extensive evidence of illegal logging, falsified data, or other major forest law infractions.

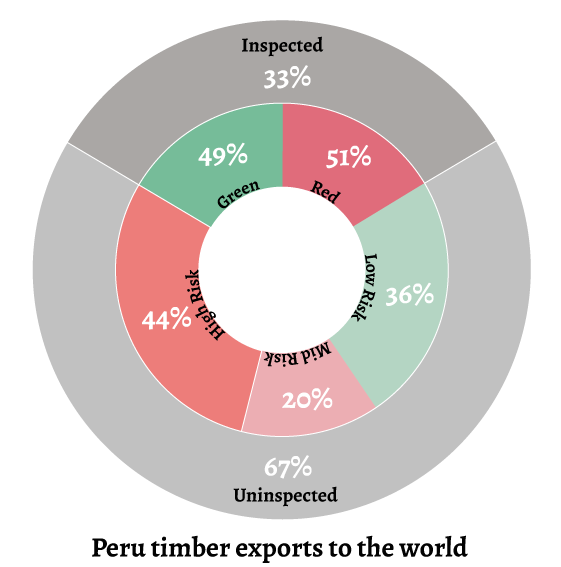

This illegally harvested wood is sold domestically and exported to other countries. The independent analyses conducted by CIEL and EIA both demonstrate that, of the 33% of timber exports from the 2015 sample inspections selected by Serfor, Peru’s forest authority, which corresponded to sites inspected by OSINFOR, 51% contained timber that OSINFOR marked as “red.” 6 Gomez, Rolando Navarro, and Melissa Blue Sky. (2017) “Continuous Improvement” in Illegal Practices in the Peruvian Forest Sector. Center for International Environmental Law. CIEL found that the proportion of illegal wood in export shipments varied by destination market. Wood from red-listed concessions represented 70% of exports to China in 2015, compared with 30% of exports to the US, for example.

EIA was also able to assess the risk level of the remaining 67% of timber exports that did not come from OSINFOR-inspected sites. Of these, EIA determined that 44% of the timber shipments were at high risk of being illegal, and an additional 20% contained moderate risk of illegality. 7 EIA assessed risk levels for harvest points that were never inspected by Osinfor by examining the green or red “sigo” status of other points of harvest from the same parcels, among other factors. For more details on the methodology see EIA (2018), p.56.

Exporters systematically launder illegal wood with fake documents, and do so with impunity.

The theft, corruption, collusion, and fraud throughout the timber supply chain in Peru is systematic, well known, and persistent in spite of attempted reforms. Rampant illegal logging in the 1990s severely depleted populations of high-value mahogany trees, leading Peru to enact a new forest law in 2000. Yet the problems continued, and in 2006 the then-forest agency INRENA estimated that 72% of the source concessions and communities for mahogany were using invented volumes, and that 92 of the 150 concessions authorized to harvest mahogany were using fraudulent documents 8 Cerdán, C. (2007). La Tala illegal de caoba (Swietenia macrophylla) en la amazonía peruana y su comercialización al mercado exterior. AIDESEP. . A 2015 documentary by news network Al Jazeera found that “buying fraudulent Transport Guides needed to sell timber domestically and export it [was] as easy as making a phone call.” 9 Abeshouse, B. and L. Del Valle (12 August 2015). People and Power: Peru’s Rotten Wood. Al Jazeera.

Unfortunately, collusion between criminals and corrupt officials has thus far prevented meaningful forest sector reform. In 2006 the World Bank described illegal logging in Peru as systematic, characterized by criminal networks in collusion with state actors 10 Pautrat & Lucich (2006). Análisis Preliminar Sobre Gobernabilidad y Cumplimiento de la Legislacion del Sector Forestal en el Peru. World Bank Group. . The same year, the US ambassador to Peru warned that “much of [Peru’s] exports are likely from illegal logging, violating Peruvian law and the CITES international convention.” In 2010 the director of INRENA acknowledged that “the corruption within INRENA is … of a magnitude that’s really incredible.” 11 EIA (2012), pp.9,10. In 2017, two years after US customs seized a shipment of illegal Peruvian wood and exposed the complicity of Peruvian officials, the Associated Press reported that prosecutions had failed to advance and officials who signed off on “falsified logging permits” remain on the job. 12 Bajak, F. (18 April 2017). AP Investigation shows Peru backsliding on illegal logging. Associated Press.

That seized shipment had been carried aboard the Yacu Kallpa, a maritime vessel that for years has transported Peru’s timber to Mexico, the United States, and the Dominican Republic. In 2014 and 2015, the Peruvian government examined the legality of the timber aboard the Yacu Kallpa under the auspices of a large-scale enforcement effort known as Operation Amazonas. Focusing on three voyages between December 2014 and November 2015, government officials found that 86% to 96% of the timber in each of those shipments was of illegal origin. 13 EIA (2018), pp 22-23.

Methodology of illegal logging in Peru

Fraud and theft can occur at every step of the timber supply chain. Below is a simplified sequence of the steps from harvest to export, alongside examples of laundering activity that may occur at each step. 14 EIA (2012), pp 26-27.

| Correct Procedures | Common Illegalities |

|---|---|

| 1. Timber is cut where there is a permit to do so, with a maximum specified annual harvest volume | Loggers cut more than allowed, and cut outside of legal cutting areas, including in National Parks and indigenous territories. |

| 2. The harvested volume is reported accurately and a valid transport permit for the corresponding volume is issued, permitting transport of that volume. | 1. Timber merchants fraudulently overstate the measurements from legally cut trees, so as to obtain transport permits that will cover yields from the combined legal and illegal trees. 2. Logging contract holders falsify forest inventories to generate “real” transport permits based on non-existing trees. 3. Traders buy black-market transport permits generated from these methods to transfer illegal wood. |

| 3. The wood is transported by river to mill towns, most commonly Pucallpa or Iquitos. At sawmills, the wood of known origins is cut into boards and new transport permits are issued. | 1.Illegal wood is mixed with legal wood at sawmills. New transport permits are issued which can obscure the actual origin. Since 2016, secondary transport permits are not required to list the point of origin. 2.Increasingly, logs are rough-cut at collection points in the jungle by mobile sawmills with even less scrutiny than in mill towns. 3.Traders buy black-market transport permits to transfer illegal wood. |

| 4. Traders in the sawmill towns select the best boards to sell to export companies. These are brought to the port of Callao on the Pacific Ocean for export. The timber and its accompanying documents are exported to over 34 countries. | Depending on the sensitivity of their market, collectors and export companies may reshuffle the documents or simply buy new documents for the wood on the black market. |

Importing Peru’s illegal wood undermines good governance, harms the environment, and hurts Peruvian communities.

Illegal logging contributes to abusive labor conditions, corruption, and violent conflict.

An International Labor Organization (ILO) study from 2005, at the height of the illegal mahogany boom, estimated that some 33,000 people worked under forced labor conditions in logging camps. The bribery, fraud, and black markets that are part of Peru’s timber trade contribute to a culture of institutionalized corruption and impunity that undermines the rule of law. In some cases, the same mafias controlling the illegal timber market are also trafficking drugs. 15 Tali, D. (22 August 2016). “Illegal Amazon loggers: ‘Anyone who buys the wood is as guilty as I’. The Irish Times.

Illegal loggers repeatedly come into violent conflict with indigenous communities, fighting to protect their lands from incursion. 16 Bedoya Garland, E. & A. Bedoya Silva-Santisteban (2005). Trabajo Forzado en la Extracción de la Madera en la Amazonia Peruana. International Labour Organization. In 2014, for example, illegal loggers killed the environmental activist and Ashéninka leader Edwin Chota, along with three of his colleagues from the indigenous community of Saweto. To date, no one has been prosecuted for this crime. 17 The last suspect was released from prison in 2016. EIA (2018) p.17, and Bajak, F. (18 April 2017).

Illegal wood is unsustainably harvested, increases carbon emissions, and threatens populations.

According to a recent study examining carbon capture and emissions from tropical forests, deforestation from human activities, including illegal logging, has turned tropical forests from net carbon sinks to net sources of carbon emissions since 2003. 18 Baccini, A. et al. Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science, 28 September 2017. The combined activity of thousands of commercial logging operations is degrading even the seemingly inexhaustible vast Amazon more rapidly than anyone would like to believe. 19 EIA (2018), p.13.

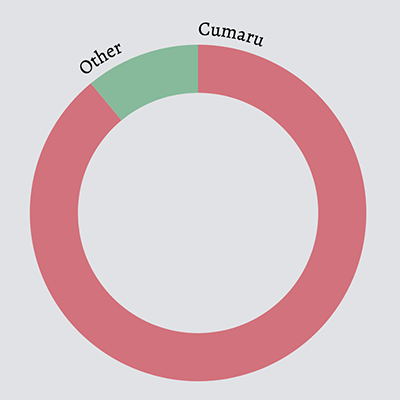

Illegal wood is unsustainable by definition, as it is usually harvested in violation of forest laws and management plans. Two formerly common Peruvian species, mahogany and cedar, have already been brought to the edge of commercial extinction. In 2015, a working group of over 90 scientists, tasked by Serfor to recommend updates to the national list of endangered flora, concluded that cumaru (known in Peru as shihuahuaco and comprising three species of Dipteryx) should be added to the list, due to its unsustainable and increasing extraction levels. 20 Letter to Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Environment, and Director of Serfor from 75 scientists. Ref: Pronunciamiento sobre la catagorización de especies de Shihuahuaco (29 November 2016). Cited in EIA (2018), p.13. The slow-growing, massive cumaru can represent up to one-third of the entire carbon sequestered in a hectare of primary rainforest, and is a vital tree for the endangered harpy eagle, macaws and other cavity-nesting birds. 21 EIA (2018), p.13., and Velez Zuazo, A. (13 December 2016). Shihuahuaco: what will be the future of this forest species in Peru? Cumaru is also Peru’s most exported species to China.

Illegal wood traps Peruvian communities in cycles of poverty.

In parts of the Amazon, the timber trade is an important source of native community income. However, loggers rarely inform communities about the legal obligations and possible sanctions, much less compensate them appropriately. Moreover, loggers often use transportation permits from native communities to launder timber, often without knowledge or consent of the communities. Soon these loggers abandon the area and leave the community to face, alone, the legal consequences for falsifications and harvest infractions. The resulting fines become financial burdens that make it impossible for communities to get out of the cycle of illegality and poverty. 22 Ibid, p.12 .

Relevance to China

China gets the largest quantity of questionable timber.

While all countries importing timber from Peru are receiving some illegal timber, not all importers are at equal risk: Peruvian government data indicates that China imports the greatest volume of illegal and high-risk wood shipments, and the proportions of illegal timber are also very high. According to CIEL and EIA’s analysis of Peru’s exports in 2015:

• China is by far the largest importer of Peru’s timber. 42% of Peru’s timber exports were to China, followed by the Dominican Republic (20%), USA (10%), and Mexico (9%).

• China imports more uninspected timber (71% of total exports in 2015) than any of the other top-5 importers. Of this uninspected timber, half is suspected to be at high risk of containing illegal timber.

• Of China’s supervised timber imports, 71% is illegal (red-listed)

• Over 89% of China’s imports by volume in 2016 were Cumaru 23 Data from SUNAT - Aduanas (National Superintendence of Tax Administration) for the year 2016., one the most commonly illegally-logged species of wood 24 Osinfor (June 2016). Resultados de la supervisiones y fiscalizaciones efectuadas por el Osinfor en el marco del Operativo International “Operación Amazonas 2015”, p 61-63.. Peruvian government foresters fear that cumaru is rapidly reaching commercial extinction, and recently recommended adding it to the list of endangered species.

China is a safety valve for dirty wood

As the US and other consumer markets become more “sensitive,” with legislation such as the Lacey Act and EUTR that demand greater evidence of import legality, Peru’s exporters have adapted by providing sensitive markets the cleanest documents and timber available, and finding a “safety valve” for the rest. As observed by CIEL, Peruvian exporters “may have identified markets who have laws prohibiting illegal timber imports and requiring companies to undertake due diligence or exercise due care, as the percentage of exports from the ‘red list’ to these countries is generally lower.” For example, “the percentage of [transport permits] on the “red list” for exports to the US and France is lower, while China and Mexico have higher percentages.” CIEL concludes: “Consumer countries without laws prohibiting the entry of illegal timber and requiring due diligence by importers allow unscrupulous exporters to exploit this weakness and export timber with [transport permits] that are on the ‘red list.’ ” 25 Gomez, Rolando Navarro, and Melissa Blue Sky. (2017), pp.1, 14.

China, which does not yet have a law prohibiting the import and trade of illegal timber, receives more timber from illegal and high-risk points of harvest from Peru than any other country. In this way, China acts as a safety valve for Peru’s illegal wood.

Other governments are acting to stop the entry of illegal wood and hold offenders accountable

A number of governments have passed laws to prevent entry of illegal wood onto their shores. In 2008, the United States amended the Lacey Act, thereby prohibiting the import or sale of illegal timber products. Under this law, they have taken multiple actions to seize or exclude illegal Peruvian timber, while continuing to investigate the trade. In 2010, the European Union passed the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR), which has sent “strong signals that illegal timber, including illegal Peruvian timber, will no longer be accepted in major markets.” 27 Ibid, pp.5, 14. Governments of the US, Norway, and Germany, have all established cooperation mechanisms with Peru to improve forest management, including by reducing illegal logging. 28 US-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement, Chapter 18, Annex 18.3.4 on Forest Governance, paragraph 1.

In 2015 and 2016, the Dominican Republic, the US, and Mexico—the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th largest importers of Peruvian timber respectively—collaborated with Peruvian authorities to detain or seize millions of dollars’ worth of illegal timber cargo. 29 EIA (2018), chapter 4: The Yacu Kallpa and Operation Amazonas 2015. As mentioned above, the US has also prohibited imports from one of Peru’s main exporters, 30 Ibid., chapter 4 and p.47; and Office of the United States Trade Representative (20 October 2017). sanctioned US entities importing illegal timber, and is currently investigating another importer. 31 EIA (2018), p.12 .

China Needs to Act

President Xi Jinping has consistently affirmed China’s commitments to leading the world in addressing climate change, reducing carbon emissions, and to pursuing an “ecological civilization” in which we “cherish the environment as we cherish our own lives.” 32 China Daily. (1 Dec 2015). Full text of President Xi’s speech at opening ceremony of Paris climate summit. China has also pledged to integrate the concepts of green development into the Belt and Road Initiative—which China has invited Latin America to join—and outlined a detailed plan for doing so. 33 Belt and Road portal. (14 May 2017). The Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan. To Latin America specifically, under the auspices of the China-CELAC forum, China has founded a partnership on “mutual benefit,” one which will promote “common sustainable development,” “sustainable use of natural resources” and collaborate on the “protection of biodiversity.” 34 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China. (April 2016). Basic Information about China-CELAC Forum. We applaud these principles and urge their application in the Peruvian timber sector.

As the world’s largest importer of Peruvian timber, and the largest importer by volume of Peru’s illegal timber, China can influence the market for legal timber more than any other country. China should require proof of legality for its imports and thereby play a leading role in pushing for a legal, sustainable timber industry in Peru.

To ensure the legality of its timber supply chain, to protect its national reputation, to show responsible leadership, to prevent harm to Peruvian communities, and to safeguard the existence of the world’s Amazon forest resources, China should cease the import of illegally sourced Peruvian timber.